The one million and the one hundred thousand: the people of Stonehenge's future

A discussion paper written by Christopher Chippindale & Brian Davison and circulated to interested parties by the Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society (Long Street, Devizes SN10 1NS; wanhs@wiltshireheritage.org.uk) in April 2001.

Purpose of this discussion paper

At present a number of working groups are examining different aspects of planning for Stonehenge's future - roads, landscape use & management, archaeology & interpretation, visitor facilities, and so on. This discussion paper draws the attention of those working groups, and of other interested parties, to a basic element which underlies all these aspects. Yet it has been overlooked so often in the past that we fear it may be overlooked once again in plans for the future. Certainly it is not conspicuous in recent briefing papers and reports.

The one million and the one hundred thousand

Central to all planning for Stonehenge is one inescapable fact: the place is world-famous and overwhelmingly popular. Currently, more than 800,000 people a year go through the turnstiles to see it, while at least another 200,000 stand at the roadside and peer through the fence. Millions glimpse the stones as they drive past on the A303 and A344.

Each visitor is different; each has different ideas about how much time, money and effort they want to spend on Stonehenge. Good planning for Stonehenge must therefore recognize the range of visitors and aim to provide what visitors of all types want. No single standardized 'Stonehenge experience' will be satisfying for all.

In this brief document, we make a first distinction by dividing this range of visitor interest into just two groups. One, about one million people in all, has a focus on the stones themselves. Of this number, a second group perhaps numbering around one hundred thousand will also take an interest in the wider landscape. Both figures are broad estimates. The first figure simply follows present visitor numbers. The second is a guess. Judging by how many visitors one encounters on the paths and open fields of the present landscape, only a very few thousand each year explore it. Attention is currently being given to opening up this landscape so as to increase that number. Even so, it is hard to believe the final number will much exceed one hundred thousand, and the more the number of visitors who are persuaded to explore it, then the less will it be a natural-seeming landscape.

The one million group we sketch in these terms. Often visiting from abroad or from other parts of Britain, these visitors have come to see the famous stones. They may want to spend much of the day elsewhere, going on to Salisbury or Bath, or driving to or from the West Country. Although interested in England and its past, they are not knowledgeable about or interested in the complexities of its landscape history, or the details concerning Stonehenge.

The one hundred thousand group we sketch in these terms. They anticipate a longer country outing, either to see Stonehenge more in the round or to enjoy walking in a chalkland landscape. They are actually or potentially interested in the less famous and lower- key monuments like the Cursus and the burial mounds, and the overall story of this landscape's history. They may want to spend much of a day around Stonehenge, and they may be well prepared for an unsheltered day out in English weather.

The difference between the two groups, and their very different numbers, is crucial because it defines what kind of provision is needed and what kind of impact it makes. If the one million go to a visitor centre but not to Stonehenge itself, then the visitor centre needs to offer such a good experience that they do not feel cheated. If the one million go to Stonehenge itself, then the means by which they get there has to be designed for that number.

All plans thus need to be compatible with a chosen balance between these numbers, and here there is a danger of misunderstanding. The grass of a quasi-natural landscape may be able to survive the trampling feet of one hundred thousand, but not of one million visitors. If there is to be a quasi-natural' landscape, then either all one million cannot go into it along the same route, or they must go across it by some means other than walking on natural grass. If plans emerge in which it is anticipated that one million visitors will follow a single route right up to or into the stone circle in a quasi-natural setting while walking on grass, then the contradiction will show itself as soon as the plans become reality (see Picture 4).

The question 'How many people doing what, where?' underlies every aspect of the Stonehenge planning. More acute in some aspects than others, it will require some difficult choices. Where provision can be made for the one million, the one hundred thousand will be able to share it as part of that larger number. Where provision can be made only for the one hundred thousand, the rest - all nine hundred thousand of them - will have to be turned away.

To illustrate this, we highlight five aspects where we fear there is particular risk of contradiction; that is, where plans may be emerging which in part anticipate one million visitors and in part anticipate one hundred thousand. Any plan which does that will unravel when it is put into practice.

Picture

1. A different generation had different ideas of what was fitting for a

Visitor Centre: this 1930s proposal is in neo-Egyptian style. For how

many

visitors? To do what there? To do what elsewhere?

Picture

1. A different generation had different ideas of what was fitting for a

Visitor Centre: this 1930s proposal is in neo-Egyptian style. For how

many

visitors? To do what there? To do what elsewhere?

1: Understanding the stones: the Visitor Centre

The selecting of architects and designers for the new proposed Visitor Centre near Amesbury has begun. If the Centre is where all visitors will start, it will brief the one million on how to reach, to understand and to enjoy Stonehenge. However, it is clear that nothing like one million people a year can enjoy the 'ideal' Stonehenge experience of walking up the ancient Avenue to the stones, and then wandering uncrowded on grass amongst the stones. So the Visitor Centre may become a destination in its own right, especially in wet weather, when the ground is soaked, offering an alternative for those who cannot safely be accommodated on grass within the real landscape or among the stones. It will also have to act as a filter, influencing or controlling the rate at which the one hundred thousand move out into the soft landscape.What is to be provided, and for how many?

Picture

2. Imber, The former village now on the Salisbury Plain military

ranges,

shows a quasi- natural chalkland landscape. A landscape like this can

accept

perhaps one hui dred thousand people a year, but fundamentals change if

it deals with one million.

Picture

2. Imber, The former village now on the Salisbury Plain military

ranges,

shows a quasi- natural chalkland landscape. A landscape like this can

accept

perhaps one hui dred thousand people a year, but fundamentals change if

it deals with one million.

2: Exploring the wider Stonehenge landscape

Central to the new vision of Stonehenge is that visitors will explore the wider landscape. But most of the one million have come to see world-famous Stonehenge, not some faint bump in a field, even if the bump is 4000 years old and the archaeologists agree to present it as a 'mystery'.

Many of those fragile monuments survive only because they are (at last) being treated very gently At the moment, perhaps only a few hundred visitors each year walk over them. If one hundred thousand people start to walk over them, they will soon become even more eroded. If one million visitors were to start their Stonehenge walk near the King Barrows, for example, those monuments would surely have to be fenced off to protect them from serious damage. It would not take many of the one million climbing on top of the barrows to start erosion.

Picture

3. Grass wear and erosion in the fields north of the stones, where some

of those walking the Stonehenge landscape converge on their final

objective.

Picture

3. Grass wear and erosion in the fields north of the stones, where some

of those walking the Stonehenge landscape converge on their final

objective.

3: Getting to the stones

Although just one hundred thousand visitors may choose to walk in the wider landscape while the rest are ferried towards Stonehenge, all one million are expected to make their final approach to the stones on foot. Any single drop-off point (whether near Fargo Plantation or on King Barrow Ridge) will concentrate wear along the obvious 'desire lines' that take the visitor towards Stonehenge. Multiple drop-off points would help, but even so the desire lines will still merge together into major trampling zones as the crowds converge on the stones.Should paternalistic 'approved routes' be hardened up, or existing ones left in place? Or should numbers be limited so as to avoid the need for this? If the approach is from Fargo, to the north-west, then the foot traffic can perhaps be concentrated on the tough surface of the old A344 highway If the approach is from King Barrow Ridge, to the north-east, there is no existing trackway The valley floor near Stonehenge Bottom, which any approach route from the north-east must cross, is specially vulnerable to 'poaching'when the earth is wet. The Avenue, the prehistoric approach to Stonehenge on its north-east axis, is a delicate thing, only surviving because it has so little been walked on. Even the one hundred thousand would rapidly destroy it as an upstanding earthwork.

Or will most of the one million not actually be allowed near the Stonehenge they have come to see?

Picture

4. We can see the impact of one-quarter of a million people walking on

grass around the eastern and southern sides Stonehenge. This was the

situation

in 1990, before the old grass and soil were removed and more resistant

grass species introduced. Today, despite moving the line of the path,

and

re-turfing when the grass perishes, that zone is still severely

degraded

- dusty in dry weather, muddy and unsafe in wet.

Picture

4. We can see the impact of one-quarter of a million people walking on

grass around the eastern and southern sides Stonehenge. This was the

situation

in 1990, before the old grass and soil were removed and more resistant

grass species introduced. Today, despite moving the line of the path,

and

re-turfing when the grass perishes, that zone is still severely

degraded

- dusty in dry weather, muddy and unsafe in wet.

4: Going around the stones of Stonehenge

Currently, only about one-third of visitors to Stonehenge (perhaps about a quarter of a million) leave the tarmac path around the western side of the stones and venture on to the grass beyond. Here the route round the stones is regularly varied to try to keep the grass alive, but even so this part of the circuit has to be closed at times to prevent the surface being destroyed. Given enough care and chemicals, more modern'goal- mouth' grass species might sustain greater wear. If, in future, one million visitors are to walk round the stones, the natural grass surface will need to be hardened up still further. Whatever is done, the ,natural' surface walked by the one million cannot be as natural as the grass surface that would be enjoyed by the one hundred thousand as they cross the landscape towards the stones.

5: Going amongst the stones at Stonehenge

The stone circle that is the central part of Stonehenge is only 30 metres across. It can safely accommodate up to 500 people at a time, but only about 250 if they wish to move around. Experience shows that the grass within the circle can withstand even these numbers only at widely separated intervals: it certainly cannot survive that level of trampling all day, every day, in all weathers. Very few of the one million visitors each year will be able to go amongst the stones if the surface is to remain a 'natural' one of healthy grass. If one million do not go in amongst the stones, even one hundred thousand would still put the grass under dangerous pressure. Some decades ago, when the grass was being trampled that way, it perished and had to be replaced by ugly gravel. When even the gravel couldn't stand the pressure, the centre of Stonehenge was closed to visitors.

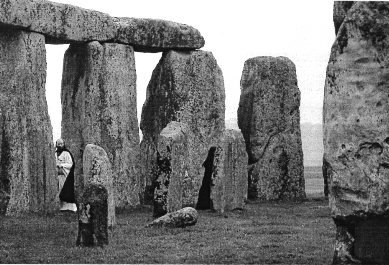

Picture

5. Stonehenge as so many of us would want to experience it, alone on

grass

amongst the ancient stones. This ideal is severely compromised if it is

shared amongst one hundred thousand per year, it is not possible for

one

million.

Picture

5. Stonehenge as so many of us would want to experience it, alone on

grass

amongst the ancient stones. This ideal is severely compromised if it is

shared amongst one hundred thousand per year, it is not possible for

one

million.

Flexibility - and humility

None of the above issues is insoluble, though some may prove fairly intractable. But all involve choices: if everyone is to go to Stonehenge, then Stonehenge will not be a quiet and empty place; if Stonehenge is to be a quiet and empty place, then not everyone can go there. Often the numbers will be neither the one hundred thousand nor the one million we have sketched here in order to differentiate different wishes and needs among Stonehenge's public. But we do ask all those planning for Stonehenge to bear the numbers in mind, and in particular not accidentally to plan a provision for the one million to use a landscape and facilities which can only work happily with the one hundred thousand.

It is salutary to remember that the last hundred years have seen huge changes in the public presentation of Stonehenge, with an average of one major scheme each generation.The present car-park and tunnel access, universally denounced today, were thought splendid when they were created - only thirty years ago.

With our number-crunching apparently at such a preliminary stage, we need to be seeking 'soft' solutions that can be fine-tuned, adjusted and even reversed when the public do not behave as any of us expected them to do. Any decisive scheme which expects to solve the Stonehenge problem for ever will, like previous decisive solutions, fail when within a few years what has been provided no longer meets visitors' needs.

About the authors

Christopher Chippindale (85 Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 IPG; cc43@cam.ac.uk) is a curator at the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology. His Stonehenge complete (2nd edition 1994) is the standard book on the later history of the place.Brian Davison (86 Lower Westwood, Bradford-on- Avon BA15 2AJ; brian@kdavison.fsnet.co.uk) was for many years a senior Inspector with English Heritage, closely concerned with the conservation and preservation of Stonehenge. He now represents the Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society on current Stonehenge working groups.